This is a story about some pants.

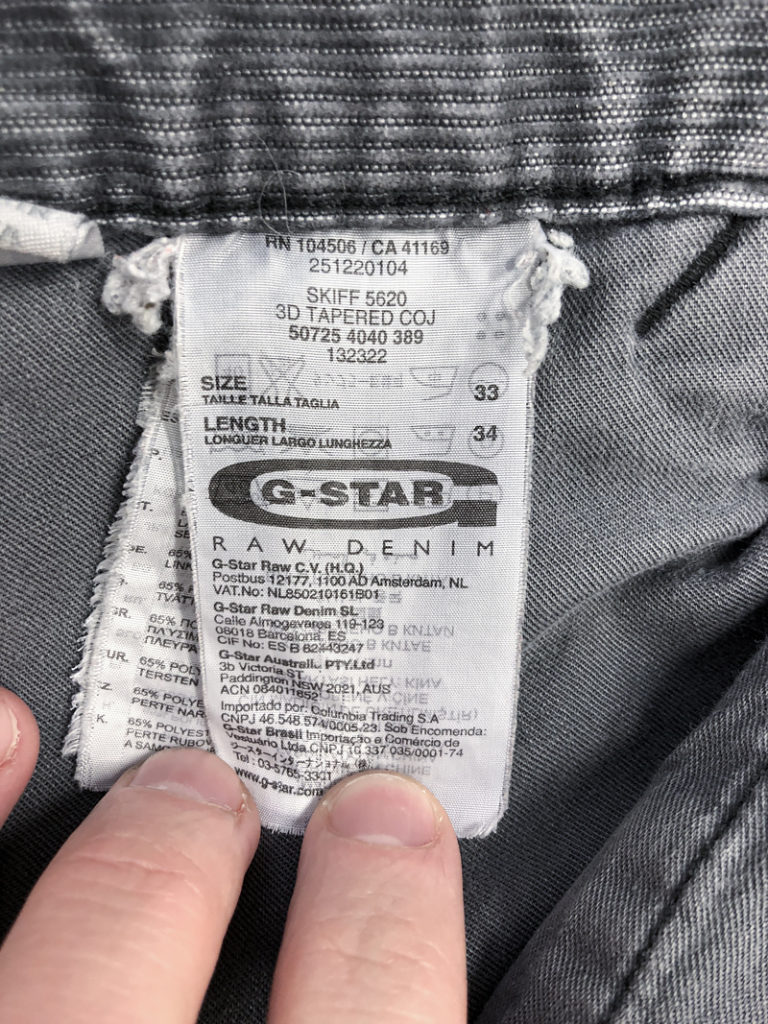

Specifically, this story is about my favorite pants that I’ve ever owned: a pair of once-blue (I think) corduroy trousers made by G-Star. I can’t recall exactly when I bought these things, except that it was closer to two decades ago than not. I wore the shit out of them , until one day I began to notice the thinnest bits getting a little too thin.

Sensing my time with these pants was growing short, I did this silly thing I do when something skyrockets to nearly invaluable status in my mind: I saved them. I stashed them in my closet and saved them for…I don’t even know what. A special occasion, I suppose? Something amazing? My instinct was just to preserve these precious pants at all costs, and figure out how to rationally deal with them later, like some sort of frozen Walt Disney head or something.

The pants remained in storage for almost a decade. They lived for years in a closet in New Zealand, then through the entirety of my time living in Oakland, finally ending up in a closet in my parents’ house. Preserved, but also sort of forgotten.

At one point during this cold storage – about a year ago or so – I asked my mom to teach me how to sew. It’s a thing she’s good at, I like learning, and I figured this would be a nice way for she and I to spend time together.

We began with a pattern for a child’s hoodie that – despite having turned out rather well – my kid outright refuses to wear.

I moved from there to a dress for Sarah, which I decided to custom-tailor for her. Learning about adjusting bust darts and easing between sizes was very fun, and three muslins later I had something that looked absolutely stunning on her…while she was standing up. Any attempt to sit in the dress was immediately met with a gut-wrenching ripping sound somewhere along the exactly-contoured side seam, teaching me the important lesson that clothes need to be functional in addition to good-looking. People move and change shape! Huh!

I eventually turned my attention to trying to make something for myself. Here’s the thing, though: there are way more interesting sewing patterns for ladies than there are for dudes out in the world. If you’re a gal, the sewing world is your oyster; there are blouses, jackets, pants, dresses, jumpsuits, each sporting all manner of interesting features that seemed fun and challenging to navigate. But if you’re a dude, your choices are basically a dress shirt, a “sport blazer”, pleated khaki “casual work” pants, or a smattering of unoffensive but boring jackets (unless, of course, one is in need of a “Cowboy” or “Royal Sultan” costume).

Lamenting this to my friend Lesleigh – an accomplished garment artist whose tenure includes Burton – she replied “Well, there’s an alternative you might try. There’s this technique called “rubbing off” a pattern. Basically, if you have a piece of clothing you like, you can take it apart and then trace around all the bits, and rebuild the garment using whatever fabric you want.”

I find this idea fascinating; it seemed like taking apart and rebuilding a car engine or something. I began scrutinizing my garments as I got dressed each morning, turning them inside out and carefully inspecting how they were made (and, more importantly, how I might non-destructively take them apart). I decided that if I was going to pursue this notion, I wanted my deconstructed garment to be challenging and interesting.

It was around this time that I was home for a week visiting my parents. “Can you take a look in your closet and see if there’s anything you can clean out of there?” my mom asked one day. And so it was that I rediscovered the perfect engine to rebuild.

The intricacy with which these pants are made is only partially-obvious from the outside. The trousers feature a distinctive “twist” in the leg, something G-Star’s jeans are known for and which is modeled after motorcycle pants. The twist feels a bit odd the first time you try on a pair of G-Star pants, but once you get used to it, there’s no going back. Unlike plebeian straight-leg designs – which look and feel fine standing up, but pucker behind the knee and rise above the ankle in a silly way when sitting – G-Star’s “arc 3d” leg (as they call it) conforms wonderfully to all manner of positions that don’t involve one’s leg being absolutely stick-straight. I love them.

Flipping the pants inside-out, however, reveals the full complexity of their construction. Several panels are lined with a double-layer of fabric, reenforcing areas like the knee, heel, and “upper butt” (technically called the “yoke”) where high degrees of wear are likely. This explains why they had lasted as long as they did, while also offering a fair bit of the “how is this put together?” puzzle-solving I’d been looking for.

At a closer distance, the pants also offer a fun amount of detail complexity. There are multiple pockets, some with flaps secured by both buttons and hidden snaps, others with false buttonholes and interesting stitching detail. A button fly added an extra element of challenge.

My first order of business was to find some blue-grey corduroy fabric – a simple and straightforward endeavor, right? I emailed my friend Rachel, the owner of what’s become my favorite online fabric shop in Chicago. “I’m looking for sort of a slate-grey corduroy, for some pants I want to make,” I asked, including some of the photos above. “Do you have anything like this?”

Her response was not what I expected: “That’s not corduroy.”

Wait, what?

“It’s hard to tell from the photos, but it looks like some sort of corded canvas or something,” she advised. “I don’t have anything like that. You might try Fishman’s, and don’t be afraid to explore upholstery sections of any other fabric shops you visit.”

I found this advice confusing. Surely she’s just mistaken, I thought. Perhaps the faded color and worn, patchy quality of the fabric wasn’t easily-explained by cell phone photos. So I packed up my pants and drove to Chicago’s south side for a second opinion.

“Can I help you?” asked an older gentleman from the cutting counter at Fishman’s as I strode through the door.

“Yeah; I’m working on a pair of corduroy pants, and was hoping you might carry something like this?” I dug the pants from my backpack and offered them to him. He regarded them only a moment before looking at me sternly over his bifocals.

“That ain’t corduroy.”

I paused, a bit unsure how to proceed. “You know, someone else told me that. I mean, if it’s not corduroy, what is it?”

The gentleman inspected the pants again. “I don’t know,” he mumbled, turning the garment over in his hands. “It looks like some sort of twill or something. Where’d you even get these?”

I felt suddenly judged.

“Th-they’re my favorite pants. Made by G-Star…” I stammered, at this point unsure how to begin describing something I thought was perfectly understandable.

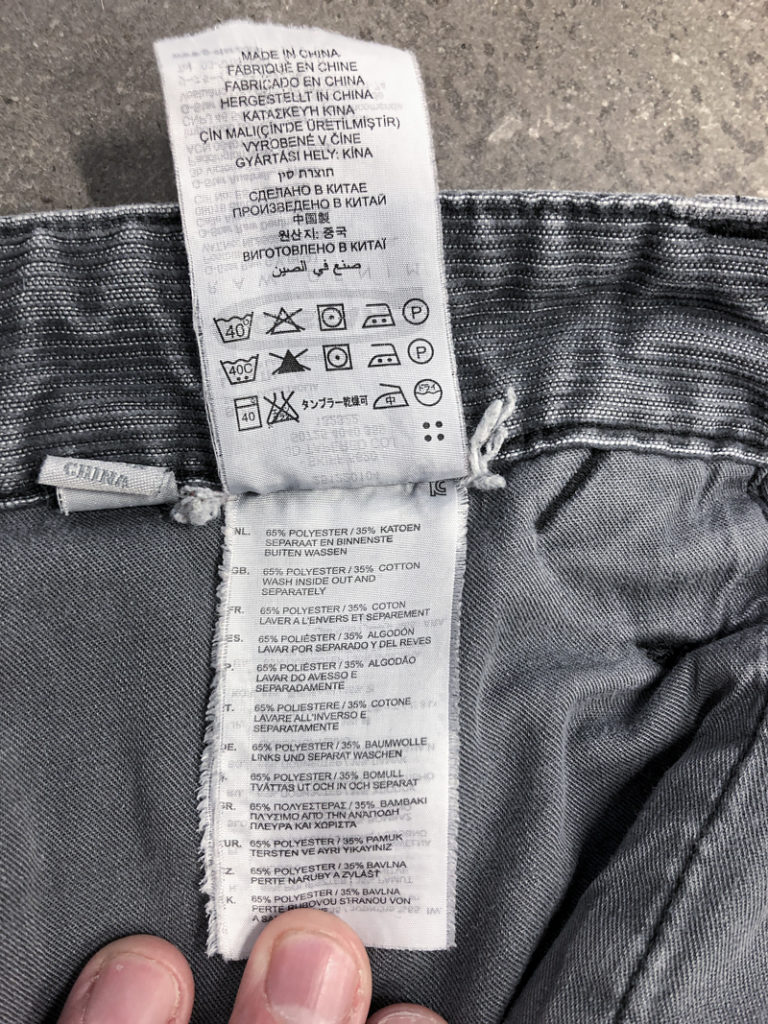

The man flipped open the waistband of the pants and read off the tag. “‘G-Star Raw Denim’…these guys make jeans?”

“Yes! They usually make jeans, they haven’t made these corduroy pants in years. They seem like an odd one-off the company made a long time ago.”

“Well, that makes sense then,” he nodded. “This is probably some sort of corded denim they made.” He continued inspecting the tag.

“Cotten polyester blend. Mmm-hmm. Yeah, you’re not gonna find this fabric.”

“You don’t have it in stock?” I asked, slightly crestfallen.

“I don’t think anyone is gonna have this in stock,” he said, handing the pants back to me.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, there are two worlds of fabric. There’s what you can buy in shops, then there’s proprietary stuff. Clothing manufacturers want to have an edge; they want their stuff to be special. So if they have the resources, they’ll often make their own special fabrics. And that fabric doesn’t get sold in stores.

“We once got a roll of fabric in here, I can’t even remember what it looked like,” he continued. “But what I do remember is two days after we got the roll, we got a call telling us we can’t sell it. Turns out it was part of a shipment used for making Disney character costumes, and it was sent to us by mistake. So Disney owned that fabric, it was their special fabric, and we would get sued if we sold it. Had to send it back.”

I was fascinated. “So you suspect that G-star had this made,” I mused aloud.

“Yeah. They probably have denim factories, they probably figured out how to make some sort of corded denim like what you have there, they made some pants until they ran out of that fabric, and probably haven’t made more since.”

As I was driving home, I replayed these comments – along with those from Rachel at Oak Fabrics – in my head. Both had used some terms I had mentally glossed over – what even is “canvas” and “twill”, and how are those different from corduroy? I suspect I was overlooking some important nuance here, so once I’d made it back to my laptop, I began retracing my steps more carefully.

A canvas, Wikipedia informed me, is a durable plain-woven fabric. It’s the “plain-woven” bit that seemed most relevant here: the term simply means that the constituent threads (properly called “yarns”) making up the fabric are arranged in a relatively straightforward under-over-under-over pattern. For most plain canvas, the threads are all the same, resulting in a uniformly-colored fabric.

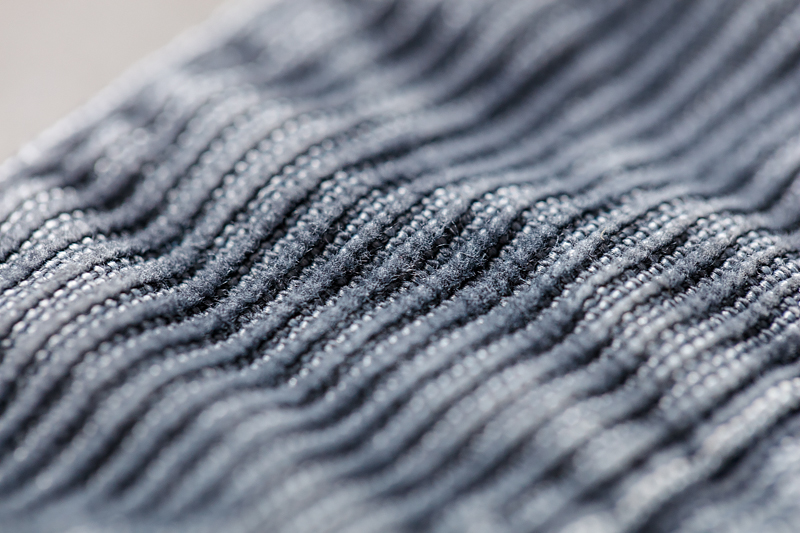

A “twill“, in comparison, follows a slightly different weaving pattern that yields both a more pleasing drape and added aesthetic interest. Denim is a style of twill in which the yarns traveling in one direction (the “weft” yarns) are dyed, while the threads traveling perpendicularly (the “warp” yarns) are left uncolored. The alternating pattern arising from the coloring and weaving style gives denim its distinctive appearance.

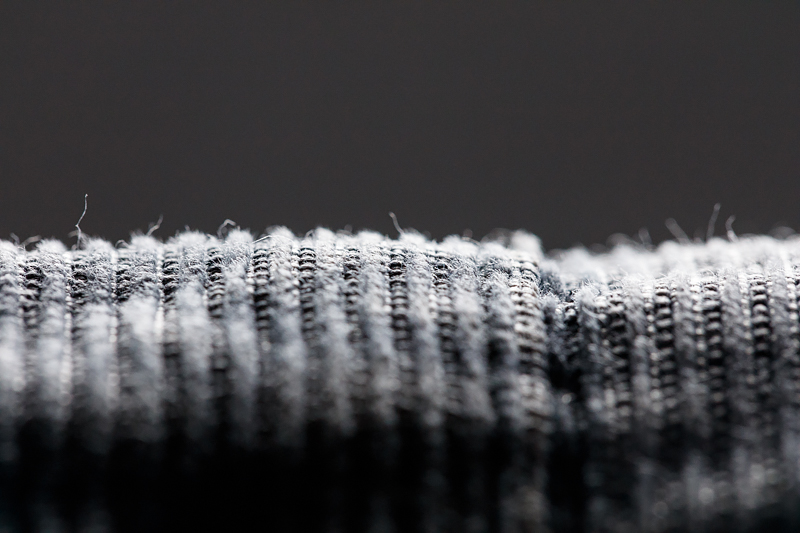

So what, then, is corduroy? It appears to be a textile that can be made using either plain or twill weaves, and including some extra “pile” yarns that give rise to the distinctive ribs along the surface of the cloth.

Learning this still left me confused, feeling the same way I feel when Kentuckians like to smugly say “all bourbons are whiskey but not all whiskies are bourbon”. What was it about this cloth that led two experts to conclude it somehow wasn’t corduroy?

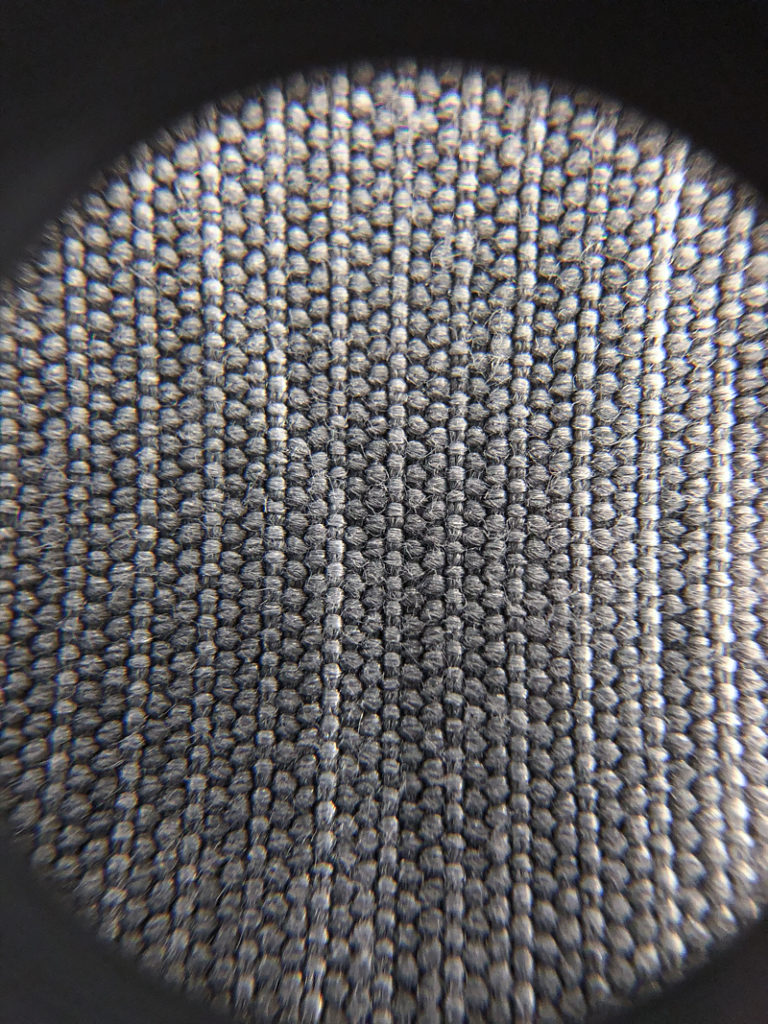

To answer this, I tried ordering a bunch of swatches of self-described corduroys of various weights, colors, and wales (this latter referring to the width of the ribs). At the same time, I pulled out a printer’s loupe to inspect my G-Star pants more closely.

This inspection uncovered something interesting: we can see in the above photos that the yarns traveling vertically are noticeably different in both color and thickness than those traveling horizontally. This differed considerably from that of the swatches I ordered – for the swatches, all the threads matched and the color was very uniform. Maybe this is what they were noticing?

I tried searching around for “corded canvas” and “corded denim”, but these terms were almost completely fruitless. The few related hits I got seemed to be from upholstery fabric shops (which is probably why Rachel encouraged I look in that direction). I found something called Bedford cord, which seems to be a relative of corduroy but didn’t seem like quite the right answer for this project.

I spent several weeks exploring my options from here. The most straightforward path forward seemed to be a cotton corduroy from Merchant & Mills. Despite it not being an exact match, it seemed reasonably similar, and a swatch confirmed it to be a lovely option.

At one point, Lesleigh asked if I’d considered just commissioning some of my mystery fabric from a weaving mill. This seemed a little ludicrous to me, but it is apparently a thing one can do. I traded emails for a few weeks with a mill here in Chicago, asking about the idea of producing a twill-woven corduroy using two differently-color yarns. As interesting as this conversation was, I was ultimately advised that the size of the order I would need to place would be quite expensive, and anyway they were not actually set up to produce corduroy.

As I was mulling this problem over, I realized that – regardless of what fabric I chose – a good bit of the challenge here was the actual act of deconstructing my pants as carefully as possible with the intent of generating a pattern from them. So, for nearly a month, I spent my evenings camped in front of our TV with my seam ripper and a small work light, carefully separating one leg of the pants into its many parts.

As I worked, I began unearthing these small, odd blemishes in the fabric.

At first, I assumed these spots must be bleach stains or something. But I eventually noticed the spots seemed to consistently be located in areas that were particularly tightly-sewn; belt loop folds, under rivets, and inside bar tacks.

I was absentmindedly staring at one of these spots one morning when suddenly it hit me what I was looking at. Several months before, I had bought a cheap tie-dye kit to make tie-dye shirts with my kid. You know how these work, right? You wrap rubber bands tightly around a shirt, dip it in dye, and the pressure of the bands prevents the dye from penetrating the tightest areas. These kits come with warnings and advisories printed all of them: “Use with natural fibers only; dye will not work on synthetic fibers.”

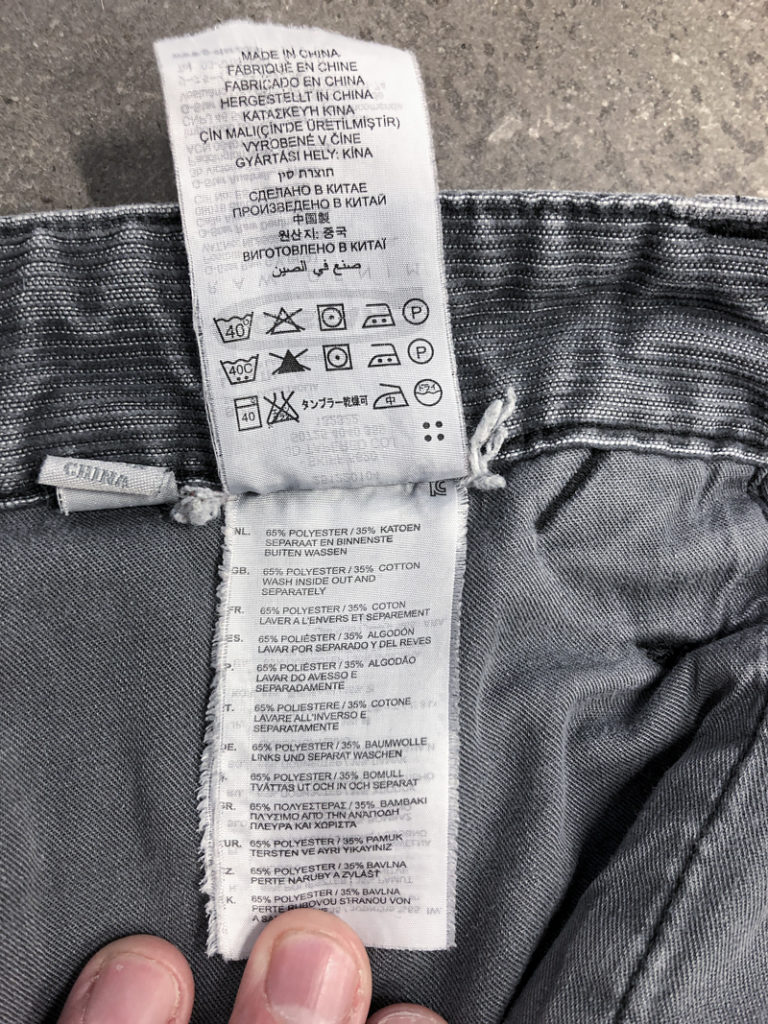

These pants, I realized with sudden euphoria, started life as white corduroy. They had been fully-assembled and dyed whole after the fact. This explained the locations of the white spots, and also why the outer corduroy and inner lining fabric were nearly the exact same color.

Most importantly, though, it explained the “twill” theory of the pants. Recalling the tag inside the waistband, which notes the makeup of the cloth:

About 2/3 of the cloth was synthetic polyester. It’s possible that G-Star used a dye that did not react to the polyester yarns exactly the same way as it did the cotton. A post-dye wash (or the subsequent decades of wear) had likely caused the two fibers to fade differently, yielding the alternating, twill look that Rachel and Fishman’s had noticed.

All this time, I had been looking for a very specific color makeup of corduroy; I should instead have been looking for a very specific fiber makeup.

I went back to both Rachel and Fishman’s, but the notion of proprietary fabric still applied. Neither had ever seen a corduroy blend like this, and weeks of searching online yielded nothing. So, despite feeling elated that I had probably solved the mystery of this fabric, I ultimately capitulated and went with the Merchant & Mills all-cotton corduroy as my choice for my rebuild. Part of me still wants to explore this rabbit hole more deeply, but at this point I was about 6 months into this adventure and decided I didn’t want to get hung up on this one aspect and risk not completing the other elements of this challenge.

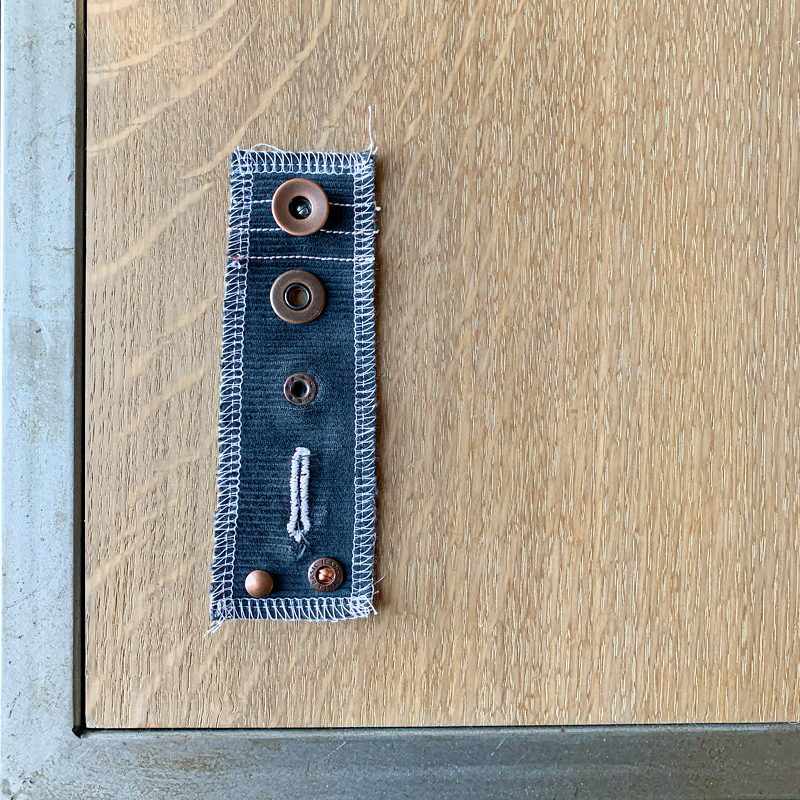

The buttons used on these pants are noteworthy; most rivet-style buttons one can find in retail fabric shops are “tack” rivets, with a solid center:

Handsome though these are, the fact that the G-Star ones were different made me curious. I learned that the hollow-center buttons are called “donut buttons”, and were popularized during WWII because they used slightly less metal in their construction. Today they are a sign of higher-quality construction, primarily because they allow one to see the two-pronged rivet that holds the button firmly in place (tack rivets only have one prong).

This style of button is surprisingly uncommon in U.S. fabric shops, I learned. Some dedicated hunting around, though, led me to this supplier in Japan. After some amount of back-and-forth with the help of Google Translate, I was able to import a selection of buttons and rivets to ponder for my pants (along with a rivet press to apply them in a tidy way).

Work pants tend to employ smaller rivets, for reenforcing high-tension areas like pocket edges and flies, where there is likely to be lots of tugging or strong pulling. In a fabric shop like Jo-Ann Fabrics, one is likely to find small tack rivets, which are fine if not a little uninteresting. I found these small button rivets quite graceful on Citron’s site, as well as these very cool open-face 2-prong rivets, these latter of which I’d never actually seen before.

I used a small swatch of my corduroy to test these out.

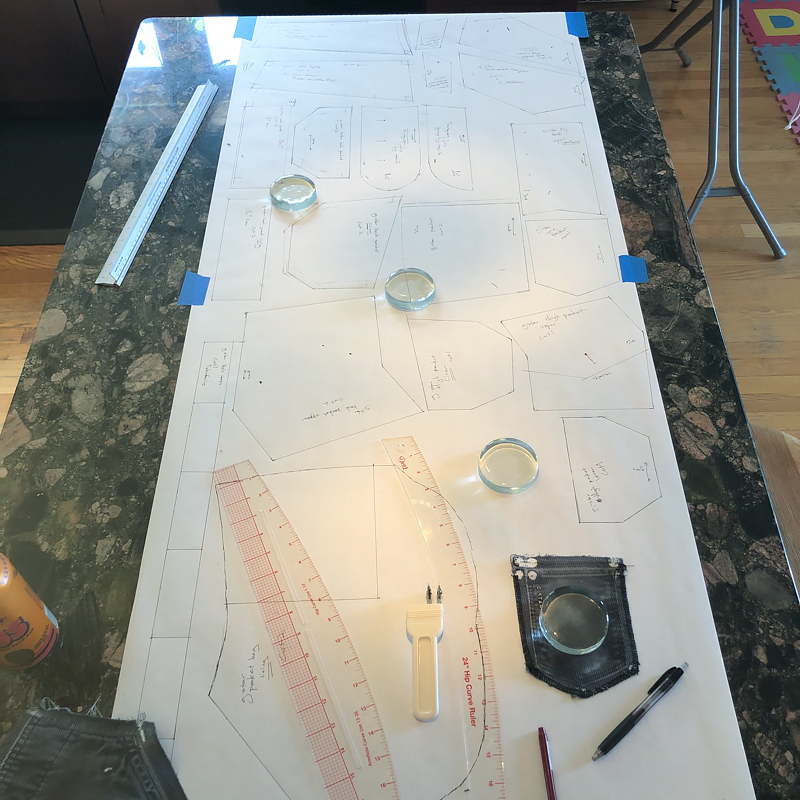

Making the pattern itself was relatively straightforward: I ironed each of my deconstructed panels flat, then traced around each onto a large roll of paper. I took care to ensure the grain of the corduroy ran straight and true before tracing, to avoid introducing any distortion or skew to the pattern.

I then carefully began the task of re-assembling my new pants, using the remaining intact leg from the original pants as a reference to verify how all the pieces fit together. Rather than using a similarly-colored fabric for my lining, I let my kid pick out a lovely lavender polka dot print.

I’m pretty ecstatic with how these turned out; they’re every bit as comfortable as my original pants, and don’t spontaneously rip open when I sit or squat in them. They’re warm and comfy for our current brisk weather and feel rugged enough to last another decade.

The original G-Star components have been safely returned to storage, this time folded neatly in a small plastic container ready for when I need to produce another copy of them…which I will look forward to doing.

And, despite my best efforts to avoid too much indulgence in reflecting on the current state of affairs of the world, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that a portion of my excess fabric has been used to fashion a face covering for venturing out of our apartment these days.

As anyone else who wears glasses and is also grappling with masks right now can attest, there’s a fogging issue with most masks that poses an annoying (at best) problem. Most masks seek to remedy this with a wire around the nose bridge; this wire is meant to be contoured around the nose to prevent breath from escaping through the top of the mask. I find this solution a bit silly and ineffective; the tension of the mask straps works against the tension of the wire, so one constantly has to find the balance between keeping the wire bent and keeping the mask tightly against the face. Elastic loops do nothing to help with this balance.

Instead, I figured if my breath is escaping through gaps between the mask and my face, why not fill these gaps somehow? I doubled a small length of bias tape and sewed it into the nose bridge of the mask, then filled this with batting to “puff” it up. This pillow works more less as intended (and certainly better than a wire), keeping my glasses fog-free as I try to navigate gas stations or grocery stores.

I discovered years ago that, when at the grocery, I am forever misplacing my pen as I shop. I ultimately developed the useful but weird-looking habit of poking my pen up into the band of my hat, where I can see it out of the corner of my eye and don’t have to stop to rummage through my pockets every few seconds. Touching a pen and then repeatedly rubbing it on my temple seems an unwise maneuver at the moment though.

So, the accent on the right side of the mask is a small loop meant to hold my pen in a similar position, secure but without touching skin. I’m aware that this is a construct of dubious wisdom, and I’m not sure I’ll end up actually using it. But it looks kinda interesting, at least.